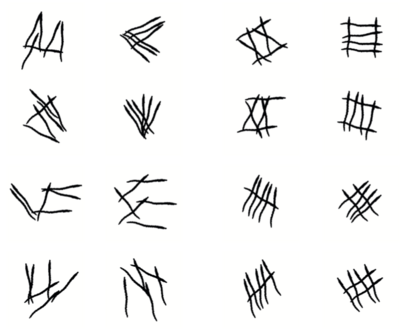

In this project, we investigate universal and cross-cultural tendencies in the production of abstract marks (drawings), through two simple drawing experiments, with participants from diverse cultural backgrounds. Experiment 1 is designed to establish whether systematic patterns emerge and how such patterns may vary at the intra- and inter-cultural level. Participants will be asked to draw lines (starting with one line in trial 1, and incrementally increasing to six lines in trial 6). The virtual drawing tool is constrained in a way to give participants some degrees of freedom (position and orientation of lines) while constraining others (length and thickness of lines).

Experiment 2 will reuse the line drawings (with 2 – 6 lines) produced in experiment 1 as stimuli in a new experiment. Here, the last line added to a particular drawing from experiment 1 will be removed, and the new participants will be asked to ‘complete’ the line arrangement by adding a new line. The new line of the participants in experiment 2 is then quantitatively compared with the original "missing" line in the drawings from experiment 1 to examine whether participants from experiment 2 will spontaneously reproduce the original pattern, and to which extend the reproduction fidelity depends on the cultural-geographical relation between the original and the new drawer.

Peolple: Christian Westh Stenbro, Izzy Wisher, Arnault Quintin Vermillet, Kristian Tylén

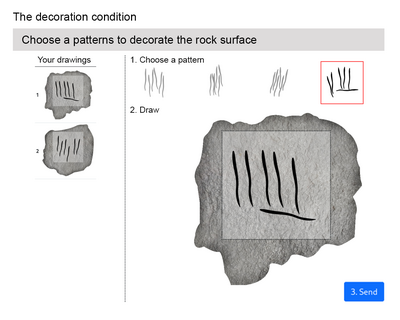

Capacities for symbolic behaviour are considered constitutive of the human species. Yet, we lack a detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which such capacities evolved. An important source of evidence is archaeological findings of markings produced on rock and bone surfaces during the Palaeolithic. Here, we systematically examined the relation between structural properties of intentional markings and their cognitive implications to support inferences about their past functions. Participants reproduced engraved markings dating to ~100.000 BP from the South African Blombos and Diepkloof sites in three conditions of cultural transmission: decoration, identity marking, and communication. Their reproductions were then used as stimuli in five perceptual experiments to investigate differences in their cognitive implications over time and explore similarities with the archaeological record. We will test the hypothesis that symbolic artefacts change in systematically different ways depending on the contexts of production, and discuss the implications for our understanding of human cognitive evolution.

People: Murillo Pagnotta, Izzy Wisher, Malte Lau Petersen, Felix Riede, Riccardo Fusaroli, Kristian Tylén

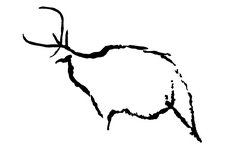

The caves of Monte Castillo in North Spain contain hundreds of drawings of animals dating back to a prolonged period of the Upper Palaeolithic. While the particular intended purpose or functions of the drawings are unknown, there are several competing accounts in the literature. In this project, we apply both experimental and data analytic methods to try to uncover systematic relationships between the distribution of visual information available in the animal depictions. We hypothesize that the particular distribution of visual information in the drawings might hold a key to the original intentions of the Palaeolithic artist.

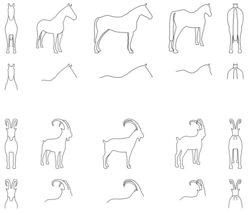

The project consists of three parts. First, we use eye-tracking to investigate where in a line drawing, spectators of figurative cave art drawings seek out information when inspecting them in different functional contexts. In particular, we compare situations where the drawings are inspected with the purpose of i) identifying the animal species, ii) identifying the animal behaviour, or iii) exploring the drawings for their aesthetic qualities. Next, we run online experiments where participants are instructed to draw animals in different conditions. Again, we hypothesize that participants' drawings will differ in their distribution of visual information (the amount of detail in different parts of the animal contour) contingent on the functional context in which they are drawn (to signify the animal species, the behaviour, or to express aesthetic intentions). Last, we model features of the online drawings to investigate properties of the cave drawings themselves. We thus explore how visual information is distributed in different parts of the animal drawings and whether this changes over time. Together, the three approaches complement each other to support inferences about the potential original intentions of the cave artists.

People: Izzy Wisher, Judy Fan, Arnav Verma, Arnault Quentin-Vermillet, Lærke Hejn Brædder, Sara Kristensen, Frederieke Nicola Wullf, Luke Ring, Murillo Pagnotta, Kristian Tylén

The Makapansgat cobble is a symmetric stone resembling a humanoid face recovered from an archaeological site in South Africa. Allegedly, it was collected and carried several kilometres into a cave by an australopithecine 3 Mya. If true, this is a unique opportunity to investigate early precursors of our capacity to understand visual representations. In this study, we derived 2-d variations of the original cobble manipulating their facelikeness and symmetry. We then used them as stimuli in an eye-tracking experiment with human, bonobo, chimpanzee, and orangutan participants to examine how these factors affect attention. Besides, these investigations were followed up with a suite of four additional experiments with the human participants investigating the emotional response, aesthetic appreciation, perceived intentionality and pareidolia effects of the stimuli.

People: Murillo Pagnotta, Daan Lameris, Juan Olvido Perea-García, Larissa Mendoza Straffon, Malte Lau Petersen, Mariska E. Kret, Riccardo Fusaroli, Kristian Tylén

In recent literature, it has been suggested that humans, in contrast to other animals (including non-human primates), will often perceive geometrical shapes in a processual way, as the generative algorithm that forms the shape. For instance, a square is represented cognitively as a repetition of four right angles. This has the implication that the visual representation of shapes is constituted by the minimal description length of the generative algorithm of the shape with simple geometrical shapes being easier to process—due to shorter description lengths—than more irregular and complex shapes (Sablé-Meyer et al., 2021). Importantly, this human-specific way of perceiving geometrical shapes is hypothesized to be grounded in a biological/genetical adaptation, giving humans a particular Language of Thought (Dehaene et al., 2022, Fodor 1975). Our study challenges these assumptions. While we in principle endorse the processual representation of shapes, we propose that it originates in the human cultural activity of actively manipulating the environment and giving shape to the world. In other words, we hypothesize that experiences with shape production will affect later shape perception and be the true source of a processual representation of shapes. In this project, we device an experimental paradigm to investigate the perceptual implications of shape production.

People: Svetlana Kuleshova, Arnault Quentin-Vermillet, Izzy Wisher, Kristian Tylén

The majority of representational cave art from the Palaeolithic consists of outline pictures of animals portrayed from a side view, which is largely thought to support effective species identification, but it may also be related to aesthetic preferences. While animals were typically depicted by nearly complete outlines, sometimes partial outlines were used to depict specific features of the animal such as the head-neck-back contour. In this study, we experimentally investigate the impact of variation in perspective (angle of depiction) and outline completeness on taxonomic identification and aesthetic rating.

People: Murillo Pagnotta, Mateusz Psujek, Riccardo Fusaroli, Kristian Tylén

Children's behaviours and their role in shaping social and cultural behaviours in the past have often been overlooked. Despite efforts to centre children in the past within an archaeology of childhood, there remains a fundamental challenge of rigorously distinguishing children's behaviours from those of adults in the archaeological record. In Upper Palaeolithic art, this has typically been addressed through an analysis of anatomical measurements of traces produced by the hands, such as hand-stencils or finger-flutings. Whilst this has succesfully identified children as artists during this period, the dependency on anatomical measurements limits the cases for Upper Palaeolithic children's art.

Focusing on the art of the Monte Castillo caves, particularly Las Monedas, this sub-project integrates developmental psychological research on children's drawings to develop a framework through which children's marks in the Upper Palaeolithic art record can be rigorously identified. Young children (ages 0-7 years old) appear to experience specific stages of mark-making as they engage in artistic behaviours. These stages are intrinsically linked with the development of particular motor abilities, thus do not seem to be merely a product of cultural influences. By utilising insights from developmental psychology and archaeology, we intend to develop specific criteria for identifying children's art in the deep past and the specific methodologies that can be employed to facilitate in-depth analyses of possible cases for children's art. Our project also intends to emphasise the intangible dimensions of children's art; the playful and narrative engagements that enrich children's mark-making behaviours.

People: Izzy Wisher, Felix Riede, John Matthews, Murillo Pagnotta, Kristian Tylén

Humans are in many ways defined by their social interactions with others. Indeed, the heart of human adaptive systems lies in peoples’ use of social networks to facilitate solutions to collective problems like resource shortfalls, information acquisition and dissemination, political turmoil, and conflict resolution. Material culture—clothing, artwork, jewelry—is often used to advertise important information about one’s personal and group identity within a social network. One way in which people do this is to adopt or manipulate the style of an object to either distinguish themselves from, or more closely identify themselves with, others. In this project, we collaborate with the NSF project “A Network Approach to Magdalenian Social Landscapes” (Egeland and Schwendler et al, UNC Greensboro, North Carolina, US) to explore how Paleolithic foragers used material culture to construct social networks and navigate the rapidly changing environments of post-glacial Europe some 18,000 to 12,000 years ago. This period, referred to as the Magdalenian, witnessed both a rapid expansion of human populations from core areas after the last Ice Age and the creation and circulation of a diversity of engraved artifacts. We seek to develop a methodology based on image analysis, artificial intelligence, perceptual experiments, and formal Social Network Analysis (SNA) to identify stylistic similarities among a widely used form of mobile art—engraved perforated disks—to explore the structure of Magdalenian social networks.

People: Chales Egeland, Rebecca Schwendler, Minjeong Kim, Arnault, Quentin-Vermillet, Izzy Wisher, Felix Riede, Kristian Tylén (and more)